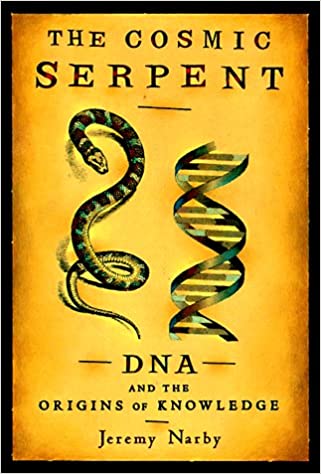

Today we’re talking about a weird one, Obscurists. This nonfiction book is called “The Cosmic Serpent,” and it’s written by Jeremy Narby.

What I love about this book:

I appreciate the sentiment in this book about keeping an open mind about things and not prejudging, which I realize will probably sound awfully hypocritical a little further on in this review. But, for now, I agree with Narby’s stance that when speaking to native people about their lives and traditions, you should listen to them, reserving judgment for as long as possible. It is certainly interesting how shamans developed several techniques to manipulate the hallucinogenics they ingest and control their biochemical effects. Though I think the author discounts how much could be achieved through simple experimentation, however imperfectly.

Alternatives on how to think about biology, other than western medicine, are, again, something I find interesting. The concept that ecology from a perspective different than what I’m used to might hold valuable insights is a tantalizing idea. A lot of research for new medicines finds their genesis after all in the world’s rainforests, and a lot of the time, it is native peoples to those regions that develop the precursors to the drugs that get synthesized in labs. True, typically, those indigenous people then get cut out of any real profit-making side of this business, but that’s a different subject that deserves its own essay.

This book does do an excellent job of pointing out that we hold a lot of local shamans and native people’s traditions on the one hand with a sort of bemused disdain. We make a show of not taking anything they have to say seriously while also fleecing them for their best ideas with the other hand. All with absolutely no sense of irony.

What I don’t love about this book:

Right at about the middle of the book—it lost me. Narby takes off onto some truly magical flights of fancy that are just nonsense. By the end, he’s accusing the scientific method of being non-objective because it dismisses what it doesn’t understand, which is precisely the opposite of the scientific method. Finding proof of a new phenomenon that can’t be explained by current models is every scientist’s wet dream because it means there is new science to be done.

He also has a pretty piss poor understanding of natural selection or only conveniently describes it poorly to support his own unsupportable positions. Toward the end of the text, he says something to the effect of “the theory of natural selection states that evolution only happens through the random collection of errors accumulated in DNA as it’s passed down through the generations, and only keeps the changes which are improvements.” The first part is more or less accurate. Still, the second part is a common misconception used by people who have an ax to grind against the concept of evolution. Natural selection doesn’t “design” anything to be objectively better at anything, it’s merely a statement that what has survived tends to pass down its traits.

Certainly beneficial traits like evolving wings or eyes can aid in survival and thus make sense as to why those traits are passed down. But if you’ve read my review of “Human Errors,” you’ll know we have some charming problems like retinas that are wired backward. Or the inherited need to desperately seek out vitamin c in our diet that most other animals don’t share with us. So no, the changes brought on by evolution don’t have to be helpful. They tend to be, but sometimes they’re just problems that don’t outright kill us before we can reproduce.

His other major point he drums that made me grind my teeth is his assertion that it’s a central tenant of western, rational thought to hold absolutely true that DNA, or sometimes he just calls it “nature,” isn’t and can’t be conscious or have intent. And then he uses that to set up a whole host of logical fallacies like Straw man arguments and appeals to ignorance, so on, and so forth. The proper “scientific” way of stating skepticism toward the idea that DNA in of itself is probably not conscious is to say that “you have not proven it is conscious,” not that it “isn’t conscious.” In science, you can prove that something does exist by demonstrating it and then repeating it in testable and measurable ways. You can’t prove the non-existence of things by demonstrating, repeating, or measuring—non-existence.

He also says that the knowledge that he can gain through the use of hallucinogenics can be tested. Great! Here’s a test, use all the hallucinogenics you want and tell me a random digit of pi out past the trillionth place that a computer could verify for us. Then do that a few more times. And if the supposed ancient alien biological technology—that DNA supposedly is—doesn’t want to answer that question, then let’s ask it what it does want to answer. If the question is too hard, then maybe we can start with what color shirt is Bill wearing in Hoboken? Surely, a globally connected decentralized super consciousness should be able to muster that.

This preview is an Amazon Affiliate link;

as an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.

Parting thoughts:

As you might imagine from above, I didn’t enjoy this book. I think it’s crucial to read things you disagree with because it’s important to know what the other side of an intellectual dispute looks like and to check your own beliefs.

While not harboring any desire to experiment with hallucinogenics, I can get behind Narby on the idea that our research into precisely how they function in the human brain is woefully thin. It’s only thin because of the conscious choice to bend, at least in the United States, to those of us of a more puritanical bent and deeming all these psychotropic drugs as icky and therefore banned.

And maybe there is a legitimate public health concern here. But it seems awfully hypocritical to me that here in the land of the free, within ten minutes walk of my front door, I can first indulge in a three thousand calorie fast food meal. Second, get a carton of cigarettes to smoke afterward, and then three chase it all down with a bottle of Jack Daniels. That there is my right as an American, no matter how ungodly destructive it is to my body, which I wouldn’t recommend. However, if I want to do acid or ingest certain mushrooms within the closed walls of my own home, that’s too far.

My point, though, isn’t to glorify drug culture or anything of the sort—none of it seems appealing to me. What I’m pointing out is that we say we have these laws because of high moral standards and character, but once new drug laws go on the books, there are always caveats and exceptions.

The real reason certain things are prohibited has nothing to do with morality, public health, or safety. It’s money. Specifically, those in power don’t stand to make any or actively might lose some if new competitors enter the marketplace to compete with their “legitimate” psychoactive drugs that they’re invested in.

No comments:

Post a Comment