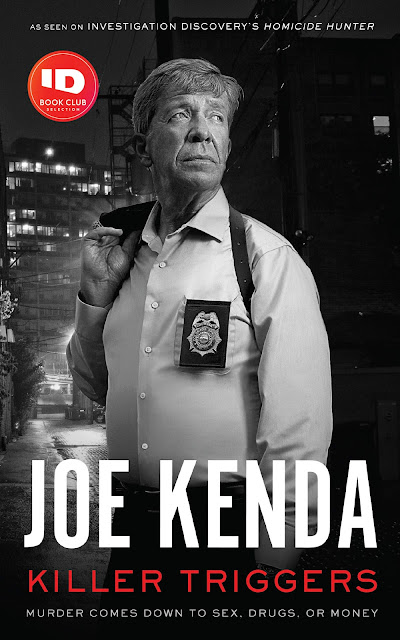

Time to dive into another true crime nonfiction, Obscurists. Today we’re talking about Joe Kenda’s “Killer Triggers.”

What I love about this book:

I love old-man stories—especially old-man cop stories. If a grandfatherly type person wants to talk about the past, I’m always down to listen. I get this is paradoxical given my views on nostalgia. How I justify the dissonance in my head is because these stories aren’t nostalgic for me. More often than not, I wasn’t even alive during these stories. They’re just history to me, and I love history.

Speaking of loves, I just love the man, Detective Joe Kenda. I’m pretty confident I would be content to listen to nearly anything he would want to talk about if I had the chance to pick his brain. There is a gruff and grim sensibility about the man, with a mix of gallows humor that is almost poetic in nature. But, aside from that, there is also a sense of duty, compassion, and practicality that I admire.

How Kenda breaks down his life’s experiences and the cases he’s investigated create vignettes into a world—thankfully—I’ve little experience with in general. It’s an interesting enough place to visit, mentally, but to face the worst humanity has to offer as a homicide detective, day-in, day-out, at all hours—I couldn’t do it.

What I don’t love about this book:

This is the second book of Kenda’s that I’ve read, and there is some overlap between the two books. Certainly, there are new details to be had, which is nice, but there were still a couple of moments when I was very much aware that I’d heard this before.

Having a long and eventful career in law enforcement, you can get a sense of Kenda’s inherent biases—not a racial bias, don’t get me wrong—but a reflexive deferment to the judgment of others in law enforcement possibly beyond what might be wise. And on one level, sure, how could he not? To survive in his world, he had to trust those professionals around him to have his back. It isn’t anything specific that he says that makes me feel this way, just the aggregate of his sentiments. Cops are the good guys, and everyone else are potential bad guys.

This preview is an Amazon Affiliate link;

as an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.

Parting thoughts:

Being a police officer grants a person a certain amount of status in any community. Whether or not that community appreciates the work done by the police is a different matter. That status, however, grants power, and power has a funny effect on people. Sometimes, but not often enough, in my opinion, people rise to the responsibility of having that power entrusted to them. Detective Kenda is one such person, by my estimate.

I am, however, skeptical of any law enforcement agency—especially one that overtly or even tacitly insists that they are beyond reproach or scrutiny. My opinion of law enforcement is about the same as the government—I see and understand the need—but just because I agree with the necessity of the institution doesn’t mean I agree with how it currently functions.

As citizens of any society, I believe it’s the people’s responsibility to hold the public servants of that society to the very highest standards. No one should get to be above scrutiny or avoid being held accountable for their actions—especially when people’s lives are in the balance.

You want to know why I’m confident the police, as a whole, aren’t nearly so infallible as they want us to trust? For every nine Americans executed, one person on death row was exonerated. That is a slightly greater than ten percent chance that any random person sentenced to death by their government was falsely convicted. No one would accept even a one percent failure rate on airplanes, trains, or cars. But for the last fifty years, we’ve accepted, as a society, greater than ten times that failure rate from the very people and system to provide impartial and dispassionate justice.

To say there is room for improvement is a vast understatement.

No comments:

Post a Comment