In this review, Obscurists, I am talking about H.P. Lovecraft’s “The Colour Out of Space.” Still, this one is a little different because I’m actually talking about three different versions of this story in one place. But I’m primarily talking about the original short story and the H.P. Lovecraft Historical Society’s Dark Adventure Radio Theatre version.

***The Non-Spoiler part of this review***

What I love about this book:

I go back and forth on whether or not “The Colour Out of Space” is my second favorite H.P. Lovecraft story, or maybe it’s “The Dunwich Horror,” anyway, today, let’s say it’s the former. On a totally unplanned and spontaneously random self-promotional note, if you read my own novel “Jade Fall,” you’ll pick up on how this story and “The Shadow over Innsmouth” influenced me.

My biggest love for this story is how it derives its horror without actually invoking the supernatural, unlike many of Lovecraft’s earlier stories. It isn’t ruled out that the meteorite comes from a supernatural source, but it isn’t confirmed or even suggested either. What it is, is simply unknowable. It’s so different and so odd that it can’t be classified when studied. I love that atmosphere of merely saying it came from outside. He doesn’t even specify outside of what, the earth, the solar system, the galaxy, the universe!?

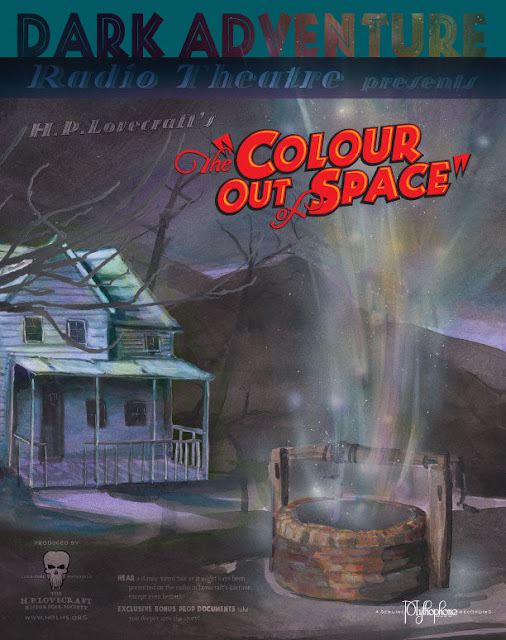

Specific to the Dark Adventure Radio Theatre version of this story, the H.P. Lovecraft Historical Society has created an updated—yet still feeling part of an older era—radio drama edition that is sublime. I’m not nearly old enough to be properly nostalgic for or even remember the golden age of the radio drama, but I love the format.

What I don’t love about this book:

Lovecraft pulls his old standby of: “It was just too horrible to describe.” And sure, there is something to be said about less is more and don’t show the monster, but he overuses that trick, and it happens in this story in more than one place.

Every version of this story that I’ve experienced at least makes use of a framing story of a surveyor making his way into the hill country around Lovecraft’s fictional city of Arkham, working on the planning stage of a new reservoir. Anyway, like I said, it’s just a framing story, and it’s an excuse to tell this outsider, and by extension, us the audience, the weird and horrible goings-on at the Gardner farm. Usually, I don’t mind a framing story, “At the Mountains of Madness,” my favorite Lovecraft story sort of employs one. I’m not too keen on this one because “The Colour out of Space” is already a short story, so it feels like words are being wasted.

Also, present in this story, there is that Lovecraft element of a casual disdain for foreigners that I always find off-putting.

Author’s Website: https://www.hplhs.org/

***The Spoiler part of this review***

***Ye be warned to turn back now***

The quick and dirty synopsis:

Like I said above, the narrative begins with a surveyor telling the tragic story of the Gardner family as it was told to him by their neighbor, a man named Ammi. The story tells of how a meteorite crashed into one of the Gardners’ fields. At first, the family’s patriarch is pleased by all the attention his farm is getting from the local scientific community—and really just the community in general.

It’s a strange meteorite too. No one can quite describe its color, just that it had a peculiar one. And it’s hot, scalding, well after it should have cooled. The strangest thing about it, though, is it shrinks as the days go on. The meteorite gets smaller and smaller every day until it’s just gone. None of the scientists from Miskatonic University have any clue what it really was when it existed.

After the meteorite disappears—shortly after—the Gardners experience an unexpected bumper crop. Their produce grows big and plentiful, but their good fortune almost immediately turns to ash in their mouths, though, because all the fruit and vegetables taste awful. It’s concluded that the meteorite must have poisoned the land, destroying the Gardners’ crops.

Things go from bad to worse when the family’s mother descends into madness—talking about odd, impossible-sounding things. People start shunning the Gardner place when they notice that animals and plants around the Gardner farm slowly transmuting into grotesqueries.

The mother’s madness spreads to the Gardner children, who become fascinated by and some even ultimately drown in the well on the property.

It gets so bad that only Ammi visits the Gardners reluctantly. On his last visit to his neighbor’s farm, the horror reaches its crescendo. The Gardner children are all dead, Mr. Gardner literally disintegrates in front of Ammi—and Ammi, without providing much detail, is compelled to put an end to the thing Mrs. Gardner has become.

Ammi reports the death of the Gardners to the authorities. He is then forced to go back to their farm with the police to investigate further. While investigating the inexplicable, the sun goes down, and things go from weird to downright terrifying as everything on the Gardner farms seems to glow. The trees around the property move and claw at the night sky under their own power.

The investigation party barely escapes with their lives as a bizarre colored light emerges from the Gardner well to return to the stars. Ammi’s horse, however, Hero, unfortunately, doesn’t survive.

Afterward, and forever after, the Gardners’ farm is referred to as “the blasted heath” because nothing ever grew there again. Ironically, it seems as if all color had been bleached out of the place—just five acres of dust and ash.

In the end, the reservoir was to be built, but the surveyor wouldn’t ever drink the new city water of Arkham, which is to be fed by it, the same water that covers the blasted heath.

Analysis:

To play devil’s advocate regarding my earlier dislike of the framing story device Lovecraft uses in this story—there is the clever twist: Can you believe Ammi’s story? Does the suspension of disbelief go that far? Obviously, the whole thing is fiction, but putting yourself in the mindset of a person hearing the story directly from the lips of the surveyor it’s still a third-hand account of the Gardner’s story. Even when the surveyor was getting the second-hand account of it from Ammi, it was decades later, and all the other witnesses to the event are long dead.

It’s an artful way of packing this story together by using the actual structure of the story as an active—if subtle—element in the narrative.

Some of that subtlety is lost in the Dark Adventure Radio Theatre version of this tale. But what I love about their versions of Lovecraft’s tales, which isn’t just true of this one, is that since the story is almost exclusively told through the dialogue of the voice actors, the characters are more robust. Lovecraft had many great qualities as a writer, but characters and how those characters talked to one another, weren’t among his strengths.

So anyone who can tap into his weird and ominous aesthetic, but make it about people I actually care about, are aces in my book.

Parting thoughts:

There is a new-ish movie version of this short story created by Richard Stanley—which, not to get too far off-topic, you should totally google image search Richard Stanley and realize that someone once said he was odd because he took too much sugar in his coffee. Ok, I’m just going to spoil it; the man dresses like Van Helsing. A Hollywood producer once said about him, you could tell he was weird by how much sugar he used in his beverage, but didn’t have a mention at all for the hat, the wizard staff, the duster—none of it—just the sugar. He took three or four sugars for the record, by-the-by, which is a lot but not like, you know, eccentric auteur artist a lot.

Anyway, back on, Richard Stanley’s take on “The Colour Out of Space” is a little bit silly, but it gives me exactly what I wanted. It was an updated take on the Lovecraft story, the characters felt like real people with established histories, and it squeezes the frame story into the main story. So the surveyor character isn’t giving us a third-hand account of how the blasted heath came to be—he is right there in it, giving us a first-hand account.

And sure, Stanley’s take of this story trades a little bit of Lovecraft’s more literary subtlety away, but what he buys with that trade is immediacy. That scene right at the end when the surveyor emerges from the rubble of the Gardners’ farm, the only survivor, covered and surrounded by nothing but white ash and dust, looks like something right out of a 9/11 documentary. Everyone who remembers that day, and the images from it, knows that look. So Lovecraft’s version leaves us with an unsettling thought and a bit of a mystery. Stanley leaves us right after jabbing us in the fearful emotional quick, which I only think he pulled off because it’s clear, even for how goofy it can be, how seriously he took this project and how much he venerated the original story.

No comments:

Post a Comment