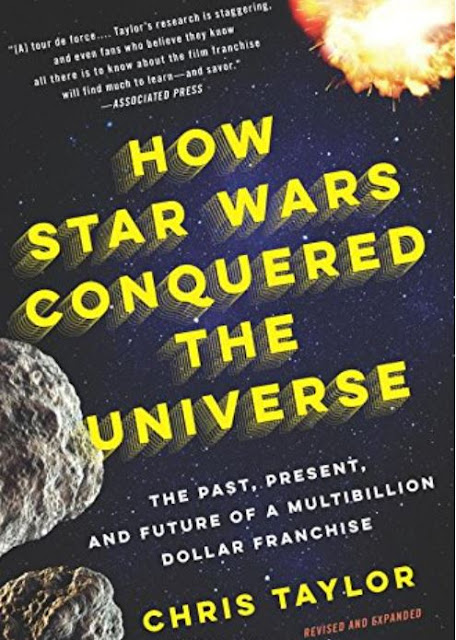

Get your lightsabers ready, Obscurists. Today, we’re talking “Star Wars” in Chris Taylor’s “How Star Wars Conquered the Universe,” a book that not just looks at the history of the epic franchise but its creator as well.

What I love about this book:

It’s no secret; I love “Star Wars,” and this is a book primarily about loving “Star Wars,” so even though it’s an incredibly obvious point to make, clearly I love this book, and felt to not address that flat out would be a disservice.

I think the primary reason why I love this franchise, which this book brings up in great detail, is the sheer escapism that this far, far away galaxy provides us that George Lucas created. For as complicated and arcane as these stories have grown into, the central thesis and messaging have remained straightforward. There is a light side and a dark side, and no matter your intentions, it’s your actions that damn or redeems you.

So this book spends a lot of time giving us a biography of the man who gave us “Star Wars.” I really enjoyed getting to know where George Lucas came from, what his early work was like, his values and flaws, and “How Star Wars Conquered the Universe” lays it all out for us.

Even more, I enjoyed the stories of not just how Lucas made “Star Wars” but the fans over the years who have loved it, as much and sometimes even more so than myself. The guys and gals who create their own film quality Stormtrooper armor have my immense respect for the dedication to their thing. And while I’d never find the time to pursue that myself—I’ve never been a cosplayer for any franchise—I’m glad to know these people are out there and form their own little communities. Something about it just tickles me. Why they choose to be the cannon fodder bad guys, no idea, but you all do you 501st legion—you’re awesome.

What I don’t love about this book:

So I don’t think any talk about “Star Wars” could be complete without talking about the fandom’s toxic undercurrent. I believe this was an important thing to bring up in this book—but it still sucks. Pretty much every entry after “Return of the Jedi” has about the same response from the fans—arguments—endless, endless vitriolic arguments. It gets quite nasty. This can lead to the labeling of “true fans,” which can lead to accusations of being “not real fans.” This might come as a complete surprise—if you’re a crustacean—but sometimes these adjudicators of who is and isn’t a “real fan” take on a chauvinistic tone. I know—shocking.

Another thing that wearies me about the fandom to “Star Wars,” which will sound weird coming from a guy who analyzes books—on a blog of all anachronistic things—is the never-ending spiraling critique/over-analysis of every single aspect of the franchise. This book is a very long book about “Star Wars’” past, present, and future, and it’s also about “Star Wars” fans and points this out about them while simultaneously engaging in that very same behavior. It is possible to love something too much—there is a fine line.

This is petty, so that’s why it’s at the end of this segment. But near the beginning of this book, there is a story about an elderly Native American man who has never seen “Star Wars” before, and he’s seeing it for the first time ever after it’s been translated into his native language. Small spoiler here, but that gentleman didn’t stay to the end, and it doesn’t seem to occur to the author that maybe he just didn’t like it. That’s what I mean when I suggest that overindulgence in fandom can be a bad thing. We have so much of ourselves wrapped up in the fandom that when we encounter someone who doesn’t like it, there is disbelief, and then we feel like they’re personally attacking us, leading to anger and so forth and so on.

This preview is an Amazon Affiliate link;

as an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.

Author's Website: https://mashable.com/author/chris-taylor/

Parting thoughts:

I’m about to share an unpopular opinion here. Gene Roddenberry, the creator of “Star Trek,” and George Lucas, within their respective franchises, were wonderfully imaginative and driven pioneers, but the quality of writing improved after their tenure in the long term. Both men, in my opinion, when given absolute creative control, with no one to check them, let their worst creative impulses flow. Roddenberry had a problem with establishing conflict in his story, and Lucas, while obsessive on specific details, was inexcusably light on others.

If you watch “A New Hope,” really just “Star Wars” back in the day, you’ll notice, if you’re honest, that the acting is a bit wooden, mainly because the dialogue is stilted. If you then progress into the next two movies, you’ll also notice that this seems to clear up and isn’t as profound a problem. But when you go and watch the prequel trilogy, you’ll notice that everyone sounds weirdly wooden again—and even more so than in “A New Hope.” So what gives?

One of the things you’ll learn if you read this book or do your own research is that Lucas didn’t have to answer to too many people in the original movie and exercised nearly complete creative control. He is also very bad at writing dialogue. I can sympathize, and it’s one of my flaws too. I would also argue that, for the most part, beyond creating archetypes, Lucas isn’t all that skilled at creating characters either.

He’s a visual guy, a fast-paced move the plot from one place to the next kind of storyteller. His most incredible skill, though, is the spectacle. Right in that first movie, he blows up a planet and then blows up the planet blower-upper by the end of the film—plus there are laser sword fights and space fighter jets dogfighting, and space wizards—and it’s just awesome. OK? So while he didn’t quite commit to who these people are, other than superficially, he can easily be forgiven.

My personal theory about the prequel movies is that they were his honest attempt at telling a more in-depth allegorical story, and they spectacularly didn’t work. They didn’t work because, by the time he set out to make them, Lucas was at the height of his creative powers, much like the Emperor. So no one was going to question the master on his opus. If they didn’t get it while he was making it, clearly, they just weren’t appreciating his genius and would see it once it all came together. That’s why they were so disappointing to many people because they never came together in the end.

What made the original trilogy so good, in my opinion, was because he was forced to work together with other people, and those people enhanced his strengths as a storyteller and smoothed his weaknesses. He was still a scrappy kid back then, and other people were around him and wanted to help him succeed, a bit like Luke.

Here is a paradoxical idea for you—I think that the George Lucas, who wrote the prequels, was a better, more mature writer than the George Lucas, who wrote the original trilogy. He had some excellent ideas woven into those stories. He started setting up some of those ideas in the first movie that most people deride as the absolute worst of the three.

The whole concept that Jar-Jar, offensive as he is, may have been a sith all along playing the fool would have been a great slow burn twist had Lucas not got cold feet because people hated the character so much. My response would have been, “they hate the character? Good, they should hate the character! He’s going to be revealed to be a sneaky duplicitous dickhead soon, and won’t they feel good that they intuited that he wasn’t a good guy.” Of course, this is marred because Jar-Jar also has an uncomfortably inexplicable racial tone to him, so I could see dropping the twist on that ground. Because to then reveal him as an evil schemer too—well, there are some problems with that messaging, to say the least.

Anyway, my point is that the prequels’ problems weren’t that George Lucas was phoning it in, or didn’t grow as a writer, or regressed. It’s that he mostly went it alone in telling the story. Pretty ironic when you think about how “Star Wars” has always been a story about a group of like-minded friends banding together to save the day and everyone who goes it alone, for individual glory’s sake, flames out to their ruin in the end.

No comments:

Post a Comment