What I love about this book:

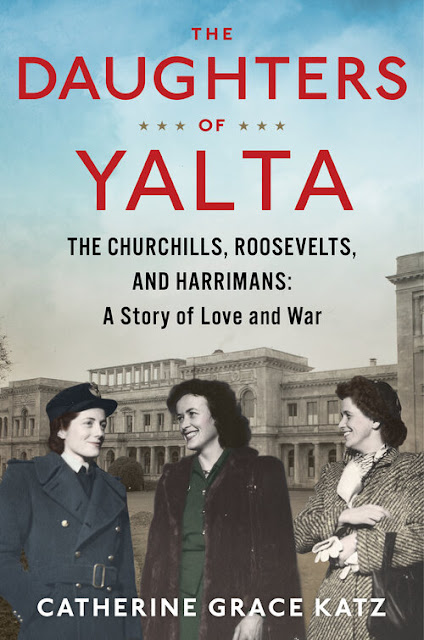

Katz shines a light on a point in history near the end of World War II that isn’t discussed much, and I didn’t know a lot about either—the Yalta conference. By telling the story from the perspectives of Kathleen Harriman, Sarah Churchill, and Anna Roosevelt, who were all present to assist their fathers, we get to see the war up close from a female perspective, which, to be frank, is often overlooked in the histories of the war.

For the meat of the book, there is a tight focus on the events immediately before, during, and around the conference. I appreciated this approach because it drives home the awkwardness of the allies meeting at Yalta. At times it feels like the allied powers preparing to take a victory lap near the conclusion of the war, and other times it feels like an odd extended family gathering. Then at other times, both of those masks fall away, and it becomes a realpolitik struggle between adversaries who barely tolerate each other. Katz captures all of that in this book.

On top of the conference’s high-level political dramatics, we get to learn about the figures involved in the conference through the eyes of their daughters. The book’s narrative is sometimes heartbreaking when you consider how Anna, finally managing to be in her father’s inner circle, has to confront the truth that her father was dying. Then there are the Churchill’s, Sarah’s own struggles in love and being so close to her father, Winston, while in the military herself. Of the daughters, though, I think I loved dynamic and fearless Kathleen the most. The fact that she basically taught herself Russian, in short order, and went to wherever she needed to be so that she could be of the greatest use—including the site of a mass grave—demonstrates the quality of the steel in her soul.

What I don’t love about this book:

There really isn’t a whole lot I didn’t love about this book, but in the area of maximum quibble, occasionally, I found it challenging to keep Sarah and Anna straight in my head. Though I think that’s less to do with the writing of the book and more just because they’re similar-sounding names, and I’m an audiobook person. So really, the fault is mine here.

I can understand an argument that the post-Yalta part of the book goes on a bit long, diminishing the effect of the tight focus earlier on in the narrative. Personally, I liked the after Yalta epilogue and getting to hear a sketch of the rest of these three women’s lives. However, for me, the chapter immediately preceding that was a bit more like marking time until Katz worked up to telling the story of the days right before and after FDR’s death.

There really isn’t a whole lot I didn’t love about this book, but in the area of maximum quibble, occasionally, I found it challenging to keep Sarah and Anna straight in my head. Though I think that’s less to do with the writing of the book and more just because they’re similar-sounding names, and I’m an audiobook person. So really, the fault is mine here.

I can understand an argument that the post-Yalta part of the book goes on a bit long, diminishing the effect of the tight focus earlier on in the narrative. Personally, I liked the after Yalta epilogue and getting to hear a sketch of the rest of these three women’s lives. However, for me, the chapter immediately preceding that was a bit more like marking time until Katz worked up to telling the story of the days right before and after FDR’s death.

This preview is an Amazon Affiliate link;

as an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.

Author's Website: https://www.catherinegracekatz.com/

Parting thoughts:

A thing that I liked in this book that I thought I would leave for this section to expand a bit more on is how there was real optimism at times, toward the end of the war, that the allies would create a better world. In my opinion, at times, even the Russians felt that optimism too, which is what makes the following decades of the cold war all the more tragic.

World War II’s legacy should have been how the world, despite its differences, came together to reject fascism, but—not to get too cynical here—that’s still a fight we’re struggling with even today. Sadly, World War II’s real legacy is the dawn of the nuclear age, which, again, could have been—if we were all a bit better—an age of new power sources for constructive ends. It wasn’t to be, though. Find me a person whose first thought when they hear the word “nuclear” isn’t “weapon,” and I’ll show you a liar.

It genuinely becomes more and more surprising to me, the more I read history, that we didn’t contrive to annihilate ourselves in nuclear hellfire before now.There’s always tomorrow, I guess. The problem with nuclear deterrence and mutually assured destruction as doctrines are they assume that the leaders are all sane—something I’m not convinced is a prerequisite to be a world leader. I think it should be, no arguments from me on that point. I’m just saying it isn’t so, which is different. But to end this digression on a more positive note, I also believe that if people, who fought and lived through World War II, could be optimistic that the world could be better, then who are we to argue? We owe it to them to try harder, be smarter—in short—be better than we have ever been so that the next group after us can be even better. That’s the point of studying history.

A thing that I liked in this book that I thought I would leave for this section to expand a bit more on is how there was real optimism at times, toward the end of the war, that the allies would create a better world. In my opinion, at times, even the Russians felt that optimism too, which is what makes the following decades of the cold war all the more tragic.

World War II’s legacy should have been how the world, despite its differences, came together to reject fascism, but—not to get too cynical here—that’s still a fight we’re struggling with even today. Sadly, World War II’s real legacy is the dawn of the nuclear age, which, again, could have been—if we were all a bit better—an age of new power sources for constructive ends. It wasn’t to be, though. Find me a person whose first thought when they hear the word “nuclear” isn’t “weapon,” and I’ll show you a liar.

It genuinely becomes more and more surprising to me, the more I read history, that we didn’t contrive to annihilate ourselves in nuclear hellfire before now.

No comments:

Post a Comment