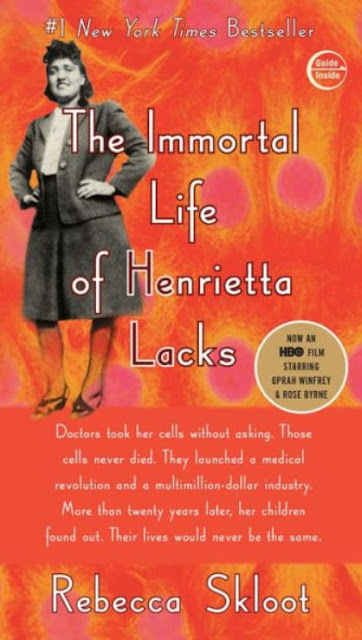

While we all have vaccines on the mind, I thought for this review we’d talk about a book about one of the lesser-known figures of medical history. All though unknowingly, she contributed to the development of the polio vaccine and so—so much more. Today’s book is Rebecca Skloot’s “The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks.”

What I love about this book:

What really captured my interest in this story was the whole concept of what HeLa cells are in the first place. They’re the oldest human immortal cell line taken from a woman named Henrietta Lacks, actually from her cervical cancer. Immortal is a loaded word but what it means in this context is the line never dies out due to old age. Given the proper environment and sustenance, they’ll continue to divide and grow forever, which is unlike normal human cells that can only divide a set number of times before the line—well—disintegrates is the quickest way to explain it. Think about that for a second, actual human material that never suffers the deleterious effects of aging—what a wild concept!

I loved learning the medical history and Henrietta’s family history simultaneously, and it’s an approach I immensely appreciated. The HeLa immortal cell line has given us so much in the way of medical breakthroughs, but Skloot shines a light on the actual person where they came from and the cost in mental anguish it took on her family.

This book explains the history of how boons to society, like Jonas Salk’s polio vaccine, relied on rigorous testing that used HeLa cells. Unquestionably, the polio vaccine was a good thing, and many other advances also utilized HeLa cells, but all of these things were possible thanks to one woman, who was left out of the history books for the most part. Addressing that blind spot in medical history is one of the best parts of this book.

Deborah, Henrietta’s daughter, by the way, is a trip. Her manic energy, when assisting and sometimes hindering Skloot with this story, adds a whole human dimension to this nonfiction about a topic that could have been presented incredibly dry. She is the human face of the source from which the medical breakthrough of the HeLa cells sprang. The most poignant thing Deborah says in this book is, “…but I always have thought it was strange, if our mother cells done so much for medicine, how come her family can’t afford to see no doctors? Don’t make no sense…”

What I don’t love about this book:

I’m not typically one for when a biographer inserts themselves in their subjects’ lives, and if you’re one of those as well, this is one of those books. It’s a very minor quibble for me, though, because ultimately, I feel that the aspects of the book that involve Deborah would have lost a lot of power had Skloot not explained their often tumultuous working relationship and Skloot’s interactions with the rest of the family.

In the vein of things I don’t like about the world that this book addresses, and absolutely needed to be included—it’s icky to find out how poorly Johns Hopkins dealt with Henrietta’s family and legacy. They’ve since improved in this area—so that’s nice.

Still, if it weren’t for Skloot, Henrietta’s family probably would have continued to languish in scientific ignorance, imagining the absolute worst Dr. Frankenstein-esque experiments being conducted on their family member. No one really took the time to explain exactly what the HeLa cells were to these people, and without a properly scientific understanding, some of them believed that in some way, Henrietta, the person was still alive. Alive and being tortured by doctors and scientists. If you can’t see why that is heartbreaking, I don’t know how to explain empathy to you. The fact that this went on for decades compounds the horror, and if I were a member of that family, I wouldn’t be a huge fan of Johns Hopkins or doctors, either.

This preview is an Amazon Affiliate link;

as an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.

Author's Website: http://rebeccaskloot.com/

Parting thoughts:

Ultimately, I believe that ethics, as applied to medicine, was the theme that resonated the most with me in this book. It often isn’t easy to know the right path, and “the greater good” can sometimes blind us to individuals’ real pain and suffering.

I haven’t mentioned it earlier in this review, but I’m sure if you’ve seen the cover of the book, you’ve realized that Henrietta Lacks was black. It’s impossible—to me, at least—to not conclude that a certain amount of why her family was treated so poorly was simple racism. It may have been unconscious, or conscious, who knows what’s in the heart of people. But it’s inescapable to me that if these cells really came from some white lady named Helen, and yes, they did try to give HeLa a white-sounding source name at one point, things would have been different.

In my broader point about ethics, my point is: what is wrong to do to one group of people is just as wrong for any other group of people. Maybe I can be accused of being overly Kantian in my ethical thinking here, given the medical breakthroughs made possible through the HeLa cells. However, I still believe people should know what parts of their bodies are being used for, even cancerous growths.

I think it’s crucial to qualify here that I agree with Skloot’s point that the study of cell cultures is absolutely necessary for medical and scientific progress. Still, there is a right way to obtain those materials, though, and that is through informed consent.

No comments:

Post a Comment